How to communicate messages at different temperatures

Radical Candor with some bumpers

It is common knowledge that one of the main skills managers need to build is communicating effectively with different audiences. There is a lot of literature available (online and in books) that gets into how to tailor your communication style to different audiences. However, one thing books leave out is how to tailor the tone and temperature of your communication based on the situation. Pressure, conflict, or disagreement situations require a different tone of voice than peaceful situations. Sometimes you want to get your frustration across to the other person (or group) clearly, but other times you might not want to just yet. This post is about how to deliver the same message at different temperatures.

But before we get into that, let's talk about the 'why?'. Shouldn't we all just speak our minds? Isn't it best to just express your disagreement directly? Aren't we required to bring our authentic selves to work? Isn't it prudent not to beat around the bush? Shouldn't we practice radical candor!!

I have been managing people for more than a decade. I have been keenly observing people even longer than that. I am not stretching the truth when I say that most of my modest success in management is directly related to being able to predict how individuals or teams will behave in war and peace situations. I have seen up close how poorly people behave in moments of conflict or disagreement.

I now firmly believe that most of the people in the workforce are not equipped to handle disagreements or conflict situations, especially if they end up on the losing side.

The stronger and longer the disagreement, the deeper the resentment in the hearts of the people who are in it, even if the outcome is a compromise that benefits both parties. Most people will remember the conflict's pain and emotional toll rather than the relief of the outcome. They will personalize the conflict. They will remember names and times.

In my career, I have always taken the approach of raising the temperature slowly, and I wholeheartedly recommend that approach to all of you readers. There have been exceptions to this when I raised the temperature in the first conversation, but they are exceptions and not the norm. When I raise the temperature slowly, it does a few things. It doesn't put people on their heels, and hence they are more open to sharing what they are actually feeling. Secondly, they will be more open to compromises and, lastly, won't hate me if they end up losing their argument.

Lots of famous technology companies say that they don't do things for the sake of social cohesion. Said another way, they don't care if employees piss each other off as long as the business keeps moving forward. That is a dangerous stance to take. I can't imagine working in a team with zero social cohesion. If your employees can't stand each other, you don't have a team anymore; you just have a bunch of mercenaries who will stab each other in the back when given a chance.

So what does raising the temperature slowly mean? In practice, it means you start off by presenting an alternative hypothesis (after fully understanding the option on the table) instead of downright dismissing the one presented by the other person (or team) and taking care not to elicit a strong emotional reaction.

Here is a real example. When I disagree with a design decision my team is making, this is what my low-temperature pushback will sound like

I am not sure this is the right way to go about it. I have seen evidence <insert_relevant_career_anecodte> that this won't work. Have we considered solving this by doing <insert_your_option>?

The highlighted words are what make this work. You are starting the conversation by not outright shooting the other person's idea down. This gentle pushback will invite a healthy, thoughtful, and objective debate instead of an unhealthy emotional response. In general, stay away from any absolutist statements. Those will almost always elicit a strong emotional response instead of robust communication.

However, there are situations when you have to increase the temperature. The only situations where raising the temperature is warranted are one-way doors or people problems. Let's look at one-way doors first.

If you believe (with rock-solid data to back up that assertion) that unwinding the decision will be prohibitively expensive, managers are obligated to increase the temperature eventually. Start with a low-temperature pushback and see if you can get your team to see your side of the equation. If it doesn't work, increase the temperature.

Here is an example of a high-temperature pushback for the abovementioned situation.

This is a bad idea, and I disagree with this decision. I have seen evidence <insert_relevant_career_anecdot> that this won't work. It will impact our company by <some_catastrophic_outcome>. We should do <insert_your_option> instead.

Just saying the words "I disagree" will elicit a strong emotional reaction from the other person. I know it is fashionable to use 'Disagree and Commit' as a conflict resolution technique, but in practice, it is very hard for people to disagree and commit without taking an emotional hit, especially if they have put in a lot of work to make their case. But in this case, it is warranted because the team is about to make a one-way door decision that you disagree with, and your previous attempts of nudging the team in the right direction didn't work.

The other situation where you might want to raise the temperature is when giving critical feedback to your team. Let's look at this example.

The work quality of one of the individuals on your team is slipping.

A low-temperature feedback will look something like this.

"Hey, I have started noticing that your work quality has been slipping. I noticed <insert_specific_examples> where you were consistently late. Do you have any thoughts on what caused the delays? What can I help with?"

A low-temperature critical feedback will empower the other person to open up lines of communication, and in the example above, the person receiving the feedback will feel comfortable sharing what's on their mind because of the tone of the feedback. One never knows what people are going through in their personal lives. Starting with low-temperature feedback will allow you to help the other person instead of putting them on the defensive.

However, if the same individual's performance doesn't improve after repeated nudges, you must raise the temperature.

A high-temperature feedback with the same individual will be something like this.

"Bob, your work has been slipping consistently. That is unacceptable and has to be rectified immediately. What do we need to do to get you there?"

The word "unacceptable" raises the temperature, and if the person still doesn't get the message, you need to go back and read this https://maheshguruswamy.substack.com/p/how-to-deliver-a-performance-improvement

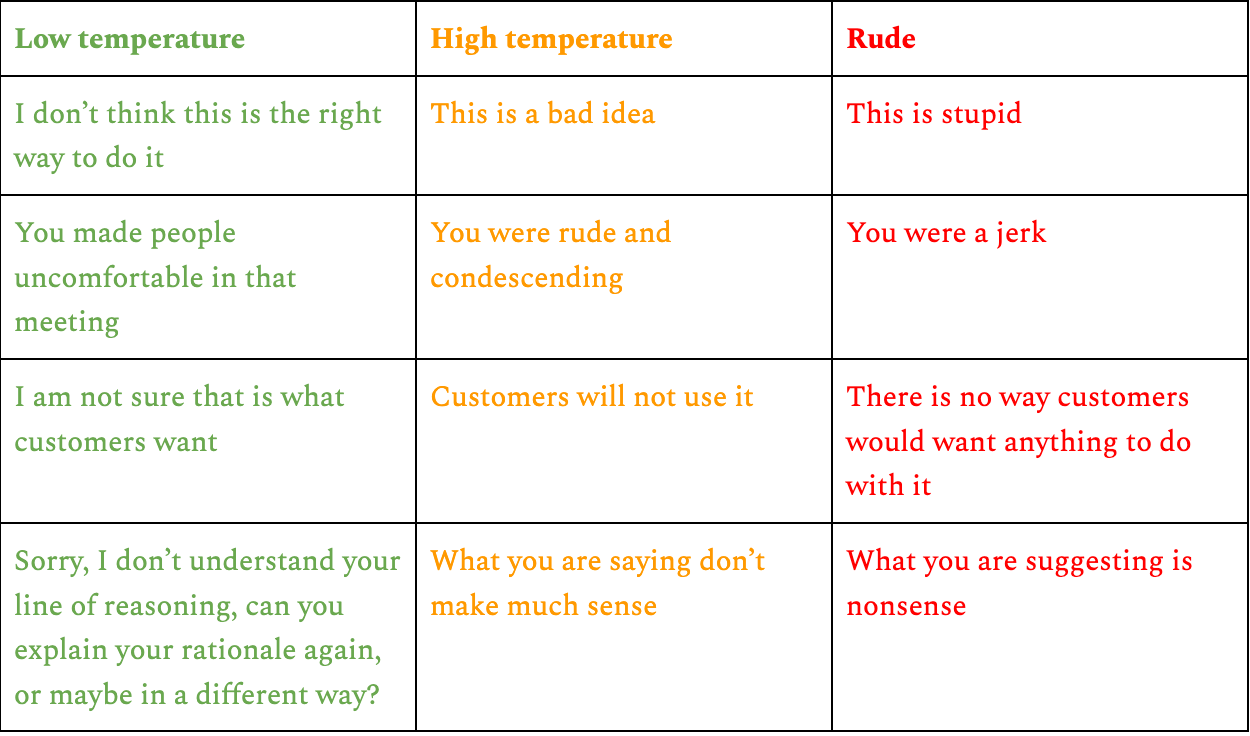

Here are some more examples of how the same message will sound at different temperatures. And yes, I wouldn't recommend using rudeness to get your point across, and yes, don't be rude even if you are right and the other person is wrong. If you ever go that far, you have to apologize to the other person.

A quick recap of takeaways from this section

Learn how to slowly ramp up the temperature in conflict situations

Low-temperature messages will encourage dialogue

High-temperature messages will elicit a strong emotional reaction, BUT it will get your point across

There is a fine line between a high-temperature message and rudeness. Don't cross it.